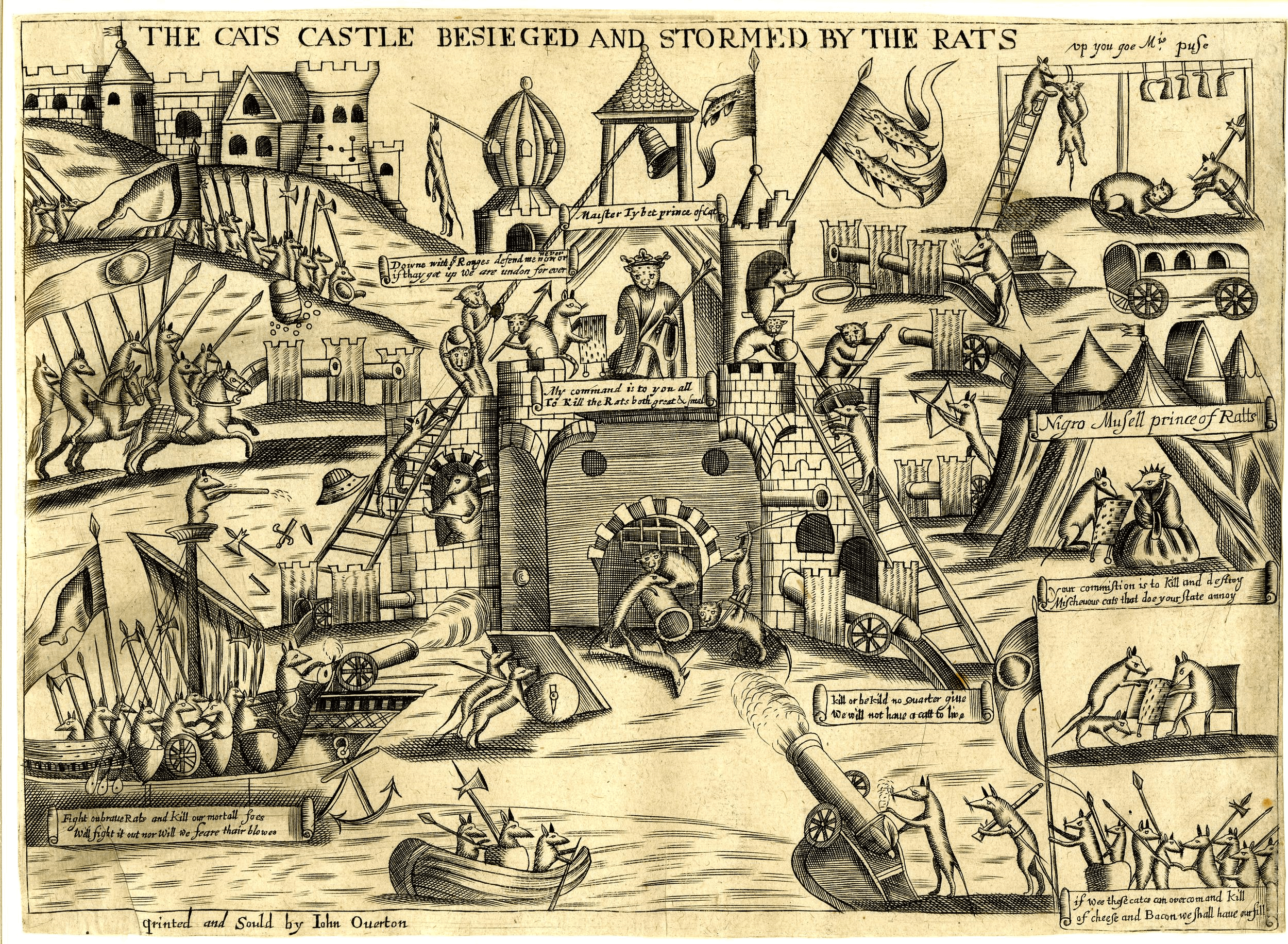

John Overton’s 1665 engraving, "The Cats Castle Besieged and Stormed by the Rats," is a complex "world turned upside down" allegory that captures the social and political anxieties of Restoration-era England.

The illustration depicts a sophisticated military operation where rats, traditionally the prey, have organized into a professional army—complete with artillery, naval vessels, and cavalry—to overthrow their feline oppressors.

At the center of the conflict is a fortified castle commanded by Maister Tybert, Prince of Cats, who struggles to defend his battlements against the relentless siege led by Nigro Mussell, Prince of Ratts.

The imagery is rich with dark humor and narrative detail, featuring cats being marched to the gallows and rats operating heavy cannons, all accompanied by rhyming scrolls that frame the rebellion as a quest for justice against "mischievous cats." Produced during the year of the Great Plague of London, the print serves as a biting satire; while its likely poked fun at shifting power dynamics and the fallibility of authority, it carries a grim historical irony, as the real-world rat population was simultaneously devastating the human population of London.

The "Cats" often represented the established authority or aristocracy, while the "Rats" represented the commoners or rebellious factions. This could be a lingering commentary on the English Civil War or the tensions following the restoration of the monarchy.

Maybe Overton was trying to depict his anger towards to the failing monarchy during the plague; in order to keep his head on his neck, the satire was the most successful weapon for him to convey his art, ideology…but also it provided “plausible deniability.” By framing a critique of the state as a whimsical fable about animals, Overton could channel his frustrations without explicitly committing treason.

If we view the cats as the Cavalier/Royalist establishment and the rats as the disenfranchised masses, the piece becomes a scathing indictment of a monarchy that felt distant and ineffective during the twin disasters of 1665: the Great Plague and the Second Anglo-Dutch War. During the plague, King Charles II and his court famously fled London for the safety of Salisbury and Oxford, leaving the “common rats” of the city to die in the streets. The image of the cats safely tucked behind stone battlements while the “lower” creatures wage war below mirrors this abandonment. By showing the rats successfully storming the castle and even hanging cats on the gallows, Overton isn’t just drawing a funny picture; he is expressing a revolutionary fantasy where those left for dead by the state rise up to dismantle the very structures that failed to protect them.

Furthermore, satire functioned as a social pressure valve. In an era where the Licensing Act of 1662 strictly censored the press, an artist couldn’t simply print a pamphlet calling the King a coward.

However, by labeling the feline king “Maister Tybert”—a name synonymous with the bumbling, arrogant cat from the Reynard the Fox fables—Overton used a cultural shorthand that the public would recognize as a mockery of the elite.

The “weapon” of satire allowed him to hide his ideology in plain sight; to a Censor, it’s a nursery rhyme, but to a frustrated Londoner living through a pandemic, it’s a call for accountability. This tactical use of absurdity allowed Overton to keep his “head on his neck” while still signaling to his audience that the “natural order” of the monarchy was neither divinely protected nor permanent.

-Tsey Alp Arslan

by alpennys

2 Comments

“Up you goe mis puSe” (miss pussy)

The more you look at it, the less it feels like a joke and more like a quiet political roast.