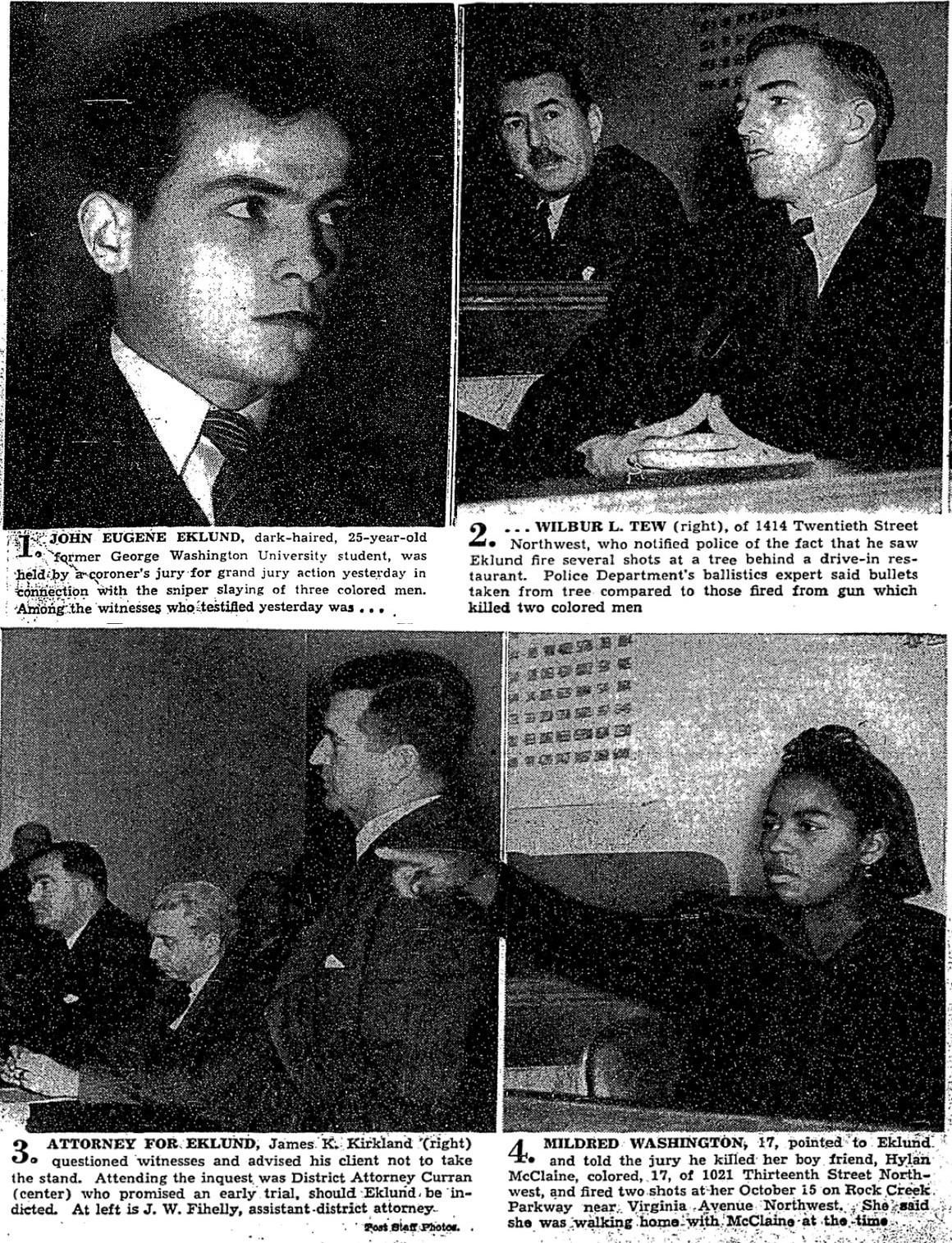

Scenes from a court hearing for John Eklund, a racist serial killer and former college student who shot and killed four black people in a series of racially motivated attacks. Eklund was identified by the girlfriend of one of his victims at the hearing (Washington, D.C., 1940) [1160 x 1514].

by lightiggy

3 Comments

>Mildred Washington, 17, had a bad feeling about the person trailing behind her and her boyfriend, Hylan McClaine, 17, as they walked over Rock Creek Park on the K Street bridge early in the morning of Oct. 15, 1940. She had reasons to be fearful. The papers were full of stories about a gunman terrorizing the Black community in Washington. The press had dubbed him the “sniper” for the way he appeared and disappeared with ease. “Oh, you’re crazy,” McClaine said. “That man isn’t thinking about us.” That man was. He lifted a .38-caliber pistol and fired three shots at McClaine, killing him. Mildred saw the assailant in the light from a streetlight and was able to describe him to police: a White man in his late 20s wearing a brown suit and no hat.

Seventeen-year-old delivery boy Hylan George McClaine, who was shot and killed while walking his girlfriend home on October 15, 1940, was the last victim in a series of attacks against black people. His girlfriend escaped unharmed. The investigation was somewhat similar to the one against the D.C. snipers 60 years later.

>In one case, police took bullet fragments from a tree trunk as evidence, just as investigators did in Tacoma, Washington, as they closed in on sniper suspects John Allen Muhammad and John Lee Malvo. In another slaying, a cryptic note was left behind. And in another parallel, baffled police appealed for the public’s help and got thousands of phone calls in return.

The first shooting was on August 30, 1940, when 23-year-old bus boy Mose Steele was shot in the back while walking home. Shortly before dying from his injuries, Steele said he thought the shooter was a white man. A day later, 35-year-old Jack Sharkey, a pinsetter at a bowling alley, was shot three times in the back while walking home. He survived his injuries. Sharkey couldn’t describe what the shooter looked like, albeit a woman nearby said she thought the shooter was black. On September 29, 28-year-old Peter McKinnie was shot and wounded. On October 6, 1940, two black men, 45-year-old Theodore Goffney and 62-year-old Samuel Banks, were both shot in the back of the head while sitting in front of Banks’ home.

[AFRO Cameraman Shows Scenes Where Four of Five Victims of Sniper Died in Washington](https://imgur.com/a/q5p1dA2)

For a moment, it seemed that just like a similar spate of shootings in 1938, the crimes would remain unsolved.

However, in November 1940, a waiter named Herbert Ray walked with police into a Pennsylvania Avenue NW cafeteria and implicated a 25-year-old white man named John Eugene Eklund. Ray told police that the former George Washington University engineering student kept press clippings about the shootings and that Eklund had discarded a brown suit matching a description by McClaine’s girlfriend. More damning was that Eklund owned a .38-caliber revolver, which matched the murder weapon. Eklund had discarded his revolver, but Ray directed the police to a tree stump that Eklund had used for target practice.

The bullets found there matched those used in the murders.

Eklund denied any involvement in the shootings, but said he disliked black people. His racism reportedly stemmed from many traffic altercations with black people and being badly beaten by black inmates while imprisoned for a series of burglary in Indiana. He had been paroled in 1939 and committed the shootings a year later. Eklund was charged with the murder of Theodore Goffney, Samuel Banks, and Hylan McClaine. He was tried solely for the slaying of McClaine since the evidence in that case was the strongest. Some Washingtonians rallied to Eklund’s support, claiming he was a victim of false charges and mistaken identity.

Potential jurors, among other questions, were asked, “Are you a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People?”

The prosecution, which said that “a deep and bitter hatred of color people” had motivated Eklund to stalk his victims, relied on circumstantial evidence, ballistic evidence, and eyewitness testimony. They had McClaine’s girlfriend, Mildred Virginia Washington, testify at the trial. She left the witness stand, placed her hand on Eklund’s shoulder, and said, “This is him.”

On the stand, Eklund recanted his previous claims of being racist, saying he had nothing against black people. He offered an alibi. His mother said he was home at the time of the murders. A black bus boy, George Randall, testified that Eklund had always treated him and fellow black employees with respect. Several other black witnesses said the same. The defense also put Percy McKinnie on the stand. He testified that Eklund was not the man who shot, insisting that his attacker was black. The prosecution attacked his testimony as unreliable, also noting the bullet matched Eklund’s revolver.

Herbert Ray testified that he had bought some bullets for Eklund and was present when Eklund hid a gun in some bushes near the old Washington airport. He said Eklund had stopped wearing his brown suit and started wearing a hat. He also testified that Eklund constantly read and talked about the shootings.

During the trial, Eklund remained calm and composed. However, he lost his composure at two points. Assistant Distracy Attorney John W. Fihelly mentioned to Eklund that while in custody, a black inmate had asked him for cigarettes. He then then said, “And didn’t you shot this to that man: ‘You black son of a bitch, if you had been out about a month ago, I’d have give you a a cigarette in the back.” At this, Eklund shouted, “That’s something the police have made up! I never said that.” When patrolman James W. Garland took the stand to verify the incident, Eklund jumped and screamed, “I wish you’d tell the truth on the stand!” When confronted with a copy of the Afro-American reportedly found in his room, Eklund said he had never seen it before and suggested that it was planted by the police.

On June 23, 1941, Eklund was convicted of first degree murder.

[The Baltimore Afro-American’s report on the verdict](https://imgur.com/a/Dc4GEVd)

Eklund received the only sentence allowed under D.C. code at the time, death in the District’s electric chair. Upon hearing the verdict, his mother cried out, “He didn’t do it! I know he didn’t do it!” The Washington Afro American reported that this was first time that a white person had been sentenced to death for murdering a black person in the District. In 1942, roughly a week before his scheduled execution, Eklund won a stay after two issues were discovered with his case. For starters, Herbert Ray had failed to disclose his prior convictions for burglary and perjury. Secondly, the police had allegedly used a Dictaphone to eavesdrop on conversations between Eklund and his attorney.

The issues were serious enough to result in a new trial.

He looks like if Fuentes and Kirk had a baby

Looks a bit like a young Ray Liota