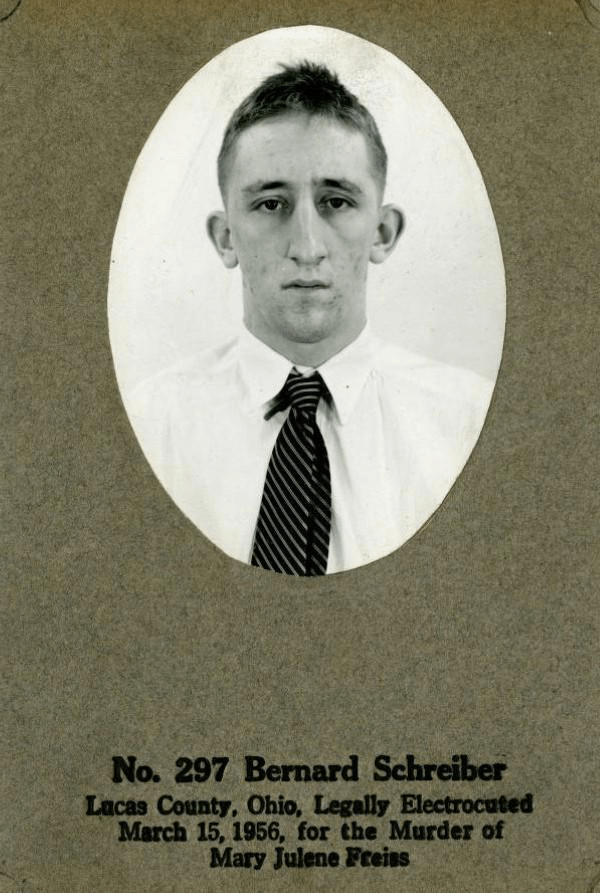

Bernard Schreiber was born in Monclova in 1937. He had never been in trouble before and was friends with several younger boys. They frequently messed with him since he had only had one date with a girl and was a virgin. So, Schreiber decided to change that. In August 1954, Schreiber and a 12-year-old companion were in Sylvania Township when a 17-year-old school girl whom they did not know, Mary Jolene Friess, rode past on a bicycle going for the mail. Schreiber immediately took a liking to her. The two boys proceeded to follow the girl for three days, watching her make trips to a mail box. On the third day, Schreiber approached Mary. The girl spurned his advances.

The next day, the two boys hid in some weeds alongside the path taken by Mary. When she rode pass, the two ambushed her. The younger boy knocked her off her bicycle by a hit to the head with a club. Mary fled into the woods, but was struck twice more and knocked unconscious. The younger boy then left the scene. Schreiber then dragged Mary deeper into the woods, tore up her clothes, and raped her. When Mary regained consciousness, Schreiber became worried that she would identify him. He stabbed the girl twice in the chest, killing her. He then went home and ate lunch.

Bernard Schreiber's arrest and confession

About a week later, the police received a tip from a neighbor, who reported that Schreiber had confessed to his mother, saying, "I just killed a girl. I stabbed her twice." Schreiber's mother said she was horrified by her son's confession, but wasn't sure what to do. After initially denying his guilt, Schreiber confessed after failing a lie detector test. Before making his statement, Schreiber took the police to a dump two miles from the scene. There, they found fragments of the girl's eyeglasses. After returning, Schreiber put his feet on the prosecutor's desk, puffed a pipe, and related how he and the younger boy had planned the crime. Sipping a cup of coffee, he talked about how they had stalked her for days.

"She looked good. We decided to wait for her. I was intrigued and aroused by the way she was dressed in bra and shorts. She had a pretty nice looking shape and that's what got me."

When confronted by the police, the younger boy cried and denied any involvement in the murder, but admitted to his initial participation.

The police asked Schreiber and the younger boy about unrelated things. Schreiber had aspired to became a Marine after his graduation. He enjoyed reading comic books, mainly about Superman and Captain Marvel, and usually stayed at home. When asked about television programs, he said he liked mysteries, "especially those which send thrills down my spine like Dragnet." He said he had no particular hobby, "but liked to fool around with carpentry and mechanics." The younger boy, described as small for his age, was called an average student and interested in sports. He'd followed his normal pursuits since the crime.

Schreiber remained at home, watching television and peering through his windows. Sheriff William Hirsch, described Schreiber, who was called "a religious-minded youth who never missed mass," as "a sort of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde." Schreiber said that he and his accomplice had driven to the scene after the body was discovered. He spent about two hours in the Sheriff's posse, "just to see how far they were getting with their investigation."

Schreiber was charged with first degree murder. He was certified to stand trial as an adult and went on trial in January 1955. He waived his right to a jury trial and entered a plea of not guilty by reason of insanity. At his trial, Schreiber said his accomplice was more culpable than he had initially claimed. What really happened, he said, was that the younger boy had told him, "Go ahead, get it over with." The boy waited at the road. When Schreiber returned to him 10 minutes later, he asked, "Are you finished so soon?"

The younger boy had not been charged. Since he had supposedly disassociated himself from the crime by fleeing after knocking Mary unconscious, he could not be held liable as an accomplice to murder or rape. On account for his age, officials did not prosecute him for assault. He had been released to his mother. At his trial, Schreiber said he changed his story after learning that if the younger boy was implicated in the murder, he could be sent to a reform school until his 21st birthday.

On the stand, the younger boy denied all involvement.

Four psychiatrists testified that Schreiber was sane, but intellectually disabled. They said he had the mentality of an 11-year-old. He was in 11th grade, but was rated at the seventh grade level. Nevertheless, Lucas County prosecutor Harry Friberg pushed for a death sentence. He said Schreiber's age, somewhat impoverished background, and learning difficulties did not warrant leniency given the brutality of the crime.

"Nevermind, and I mean never, should this man be in a position to commit a similar crime again."

He noted that Schreiber had used a hunting knife, not a pocket knife.

A three-judge panel deliberated for an hour before finding him guilty of first degree murder and sentencing him to death by electrocution. A plea for a second degree murder conviction or at least an attachment of mercy to a first degree murder conviction were rejected. Schreiber had admitted to stabbing Mary a second time since he thought he'd missed her heart the first time. Upon hearing the sentence, Schreiber dropped his head and closed his eyes. His mother became hysterical and his two sisters sobbed. Schreiber later said the decision felt "just like they had shoved a knife in me."

On June 28, 1955, an appellate court confirmed the verdict in a 2-1 decision. On December 14, 1955, the Ohio Supreme Court rejected his appeal and scheduled his execution for January 13, 1956. On December 30, Governor Frank Lausche delayed the execution to March 15 so that Schreiber could ask for clemency. At a hearing in January, defense attorney Marcus L. Friedman told the Ohio Pardons and Parole Commission that Schreiber had been raised on the edge of poverty and never had a real break in his life. Friedman said clemency would be "the first and last break he'll ever get."

"If he gets one now, he will never get another because he will be in prison the rest of his life."

This was not true. Life without parole did not become a sentencing option in Ohio until 1993. Any sentence less than death for Schreiber was virtually guaranteed to result in him being paroled in the 1970s or 1980s.

That aside, Friedman noted the presence of other mitigating factors, such as Schreiber's age and learning difficulties. The panel was unmoved. On March 15, Schreiber lost his last hope of avoiding execution when Governor Lausche said he would not intervene. After counseling with his cabinet and reviewing the case, he announced, "Based upon a careful study of the evidence in the case of Bernard Schreiber, I find the facts to be of a nature not warranting my intervention. The decisions respectively of the Common Pleas. Appellate and the Supreme Courts will not be disturbed."

Schreiber received a final visit from his family. His mother, a brother, and a sister came to say goodbye. His last meal consisted of fresh shrimp cocktail, roast prime ribs of beef, french fried potatoes, buttered whole greens, head lettuce with mayonnaise, pumpkin pie with ice cream, hot rolls and butter with strawberry preserves, coffee, milk, and Coca-Cola. A request by Schreiber to be allowed to eat his last meal with a prison buddy was granted. He ate with 26-year-old Benjamin Meyer, who had been convicted of murdering his estranged wife, 26-year-old Velvia Meyer, on February 15, 1954. Meyer had murdered his wife about two months after she initiated divorce proceedings against him. The two had gotten into a heated argument when Velvia refused to withdraw them. It ended with Meyer shooting Velvia, the mother of his five children, three times with a revolver.

At his trial, Meyer had argued that he was only guilty of second degree murder. He said the gun was meant for himself if his wife didn't drop the divorce proceedings.

"Meyer wants you to believe he did the slaying in an unconscious state as the result of being struck on the head by a club."

The prosecution said the crime was premeditated, noting that he had fired three shots and had previously spied on his wife. He had also initially lied to the police, saying he only shot his wife after she struck him with a club. In reality, his wife had done nothing. He was really struck by his wife's niece, 17-year-old Delores Sniff, with a hairbrush. Meyer said she had struck first, but couldn't remember much about what had happened. Delores testified that Meyer had arrived to her home uninvited and pushed his way inside. Her mother, Leila Sniff, said Meyer wasn't supposed to be there and that he should call the police, but did nothing. Meyer left the house, but was twice seen by Leila going around the back. Leila told him that her sister would be here soon and to wait at the front porch.

When his wife arrived, Meyer confronted her and pleaded with her to drop her divorce proceedings. She replied that they had tried reconciliation before and it "wouldn't work." When Meyer insisted, she said, "It is out of my hands." At this, he replied, "I can do something about it, drew his revolver, and shot her. Delores started hitting Meyer with her hairbrush, but stopped when he turned the gun on her. Meyer did not hurt Delores, but did shoot his wife twice more before fleeing. Assistant prosecutor Phil Henderson said the idea that Meyer was struck first was a "concocted story". He asked the jury to feel Delores's broken hairbrush in their hands to judge whether it could've hurt Meyer. Prosecutor Fred Murray also said Meyer had a bad conduct record in the Navy and was defiant against authorities. Six months prior to the murder, he had been fined on a charge of assault and battery filed against his wife.

"What did he think of them and his wife? The pattern is clear that Benjamin Meyer has no respect for law and order."

Murray noted that Meyer had bought the gun on the day of the murder: "Meyer proceeded in cold blood to take his wife's life, and shot twice more to make sure of it."

Murray dismissed the claim that the gun was for suicide. In regard to a previous suicide attempt by Meyer a month prior to the murder, he described it as a half-hearted attempt intended to guilt-trip his wife into dropping her divorce proceedings and said that Meyer didn't have the guts to kill himself. He also said that Meyer's decision to flee and conceal the weapon indicated his awareness of what was happening.

Meyer was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to death after the jury declined to recommend mercy. He was the first person sentenced to death in Hocking County in the 20th century. However, on September 20, 1955, just three days before his scheduled execution, Governor Lausche commuted his sentence to life in prison after a campaign from his parents. Lausche had repeatedly delayed the execution as Meyer's parents pleaded with him to consider their son's circumstances. Lausche gave this explanation for his decision.

"Through difficulties and misunderstandings in the home, they had been separated on several occasions. During the last separation, he visited wanting her to come back; a further misunderstanding occurred at the end of which he took her like through a gunshot. When they were married on Nov. 23, 1945, he was 16 years and nine months of age and she was 18 years and nine months. Within the first seven years of their marriage, five children were born. At the time of the tragedy, he was 24 years of age and already the father of five children. He was skilled in no trade or craft and started laboring in a factory when he was 16 years old. The task which fell upon him and his wife was extraordinarily heavy. Misunderstandings and bickerings were inevitably to occur. He was not equipped either by age or position of a trade or economic background to assume his huge responsibilities. With the full recognition of the seriousness of the crime and the sorrow he has brought upon the relatives of his deceased wife, in my opinion, the ends of justice will be served by the State of Ohio exacting of him imprisonment for life instead of death by execution."

Meyer was paroled some time between the late-1970s and mid-1980s.

His younger friend would not be so lucky.

Bernard Schreiber, 19, was executed by electrocution at the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus on March 15, 1956. He had no last words, but quietly recited the Lord's prayer with two priests as he was strapped into the electric chair. Schreiber, who was 17 years and 11 months old at the time of the murder, was the last juvenile offender to be executed in Ohio. When the state reinstated the death penalty in 1981, lawmakers banned it for juveniles, solidifying his morbid historical footnote.

by lightiggy

4 Comments

[Capital Punishment of Children in Ohio: “They’d Never Send a Boy of Seventeen to the Chair in Ohio, Would They?”](https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1823&context=akronlawreview)

Between 1880 and 1956, 19 juvenile offenders were executed in Ohio, all for murder.

All but one were at least 16 at the time of their crimes.

The exception was 16-year-old Gustave Ohr, who was hanged in 1880 for robbing and murdering a man when he was fifteen. Hanged him were his accomplice, 17-year-old George Mann, who was 16 at the time of the murder, and 18-year-old John Sammett, who was 17 when he murdered a 16-year-old boy who testified against him in a burglary case. Even in 1880, some had pleaded for mercy on behalf of the three boys, who were the first juvenile offenders to be executed in the state. Over the next 76 years, judges and juries in Ohio had become increasingly reluctant to condemn anyone that young to death.

Schreiber’s near-adulthood contributed to his death sentence. Of the 19 executed juvenile offenders, he was the second oldest (one was only three days shy of his 18th birthday). At the trial, the prosecutor had perceived and described Schreiber, now 18, as a young man, not a child. In a twisted way, the prosecution gave him what he wanted. Schreiber had wanted to “prove his manhood” and he was now being treated like a man.

[Ohio Will No Longer Sentence Kids to Life Without Parole](https://theappeal.org/politicalreport/ohio-ends-juvenile-life-without-parole/)

In 2021, nearly 65 years after Schreiber’s execution, Governor Mike DeWine signed legislation to heavily restrict life terms without parole and long prison terms for juveniles.

The law grants parole eligibility to juvenile offenders in 20 years for those convicted of non-homicide offenses, 25 years for those convicted of a homicide offense, and 30 years for those convicted of two homicide offenses as the principal offender. Two exceptions were carved out to deny early parole eligibility to juvenile offenders convicted of murder in furtherance of terrorism or of three or more intentional homicide offenses as the principal offender. The “principal offender” distinction is important.

The exception was intended for the likes of T.J. Lane, who was 17 when he murdered three classmates in a school shooting. At sentencing, Lane wore a t-shirt with the word “killer” written on it, then mocked and made obscene gestures at the relatives of his victims. Since Lane committed the mass shooting on his own, he is considered the principal offender. In contrast, serial killer Brogan Rafferty, who was 16 when he participated in the murders of three men who were lured to their deaths on via fake job offers at a non-existent farm on Craigslist, would not be considered a principal offender.

This is because Rafferty participated in these crimes under the influence of an older and more culpable accomplice, [Richard Beasley](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Beasley_(serial_killer)), who was in his early 50s. At his original trial, Rafferty’s lawyers tried to suppress his confession and said went along with Beasley out of fear for his life. Their defense was rejected and he was convicted of three counts of aggravated murder. Judging by their statements at the sentencing hearings for the two, even the relatives of the victims knew that Beasley was more culpable.

Beasley had maintained his innocence in spite of security camera footage of him meeting with the victims, a digital trail of the fraudulent job ads and communications with the victims, him stealing the identity of the first victim, the confession of Brogan Rafferty, and the testimony of Scott Davis, Beasley’s intended fourth victim.

>”On November 6, 2011, you shot me several times like I was a rabid dog,” Davis said. “You are a liar, a thief and a murderer.”

>

>”He’s an animal, nothing but an animal, I told you before, he murdered our son for $5. That’s what it was…five dollars,” said Jack Kern, the father of victim Timothy Kern.

Rafferty did not deny his guilt:

>”I thought it was something horrible,” a grim-faced Brogan Rafferty, 17, told Judge Lynne Callahan before he was sentenced. If his life has been hell since the killings last year, “They must be living in it,” said Rafferty, gesturing with his cuffed hands at victims’ relatives who crowded the court. He said they also were victims of his crimes.

>

>”There were many options I couldn’t see at the time,” said Rafferty, who remained composed during the sentencing, watching with a slight frown as relatives of the victims addressed the court. “You know nothing of remorse, you know nothing of shame,” Barb Dailey, sister of Timothy Kern, told Rafferty in an eye-to-eye confrontation just steps apart. Without true repentance, “You will be destroyed,” she told Rafferty, who nodded slightly. Lori Hildreth, sister of the lone survivor, Scott Davis, 49, read a statement from him as Rafferty’s mother sobbed.

>

>”It was only by the grace of God that I survived,” Davis’ statement said. “You took from me a chance to have a normal life.” Davis’s statement reminded Rafferty that they shared a meal before he was wounded and said Rafferty had a chance to “stop what was about to happen.”

Beasley was sentenced to death. As for Rafferty, there had initially been talks of him receiving a life sentence with parole eligibility after 30 years in exchange for testimony against Beasley. After negotiations fell apart, he was sentenced to life in prison without parole. In an interview in 2013, Rafferty said he was resigned to his fate.

[‘I’m Supposed to Be Dead Anyway’: An Interview With a Teenage Convict](https://archive.is/cbd41)

>When a judge sentenced then-17-year-old Brogan Rafferty to life without parole for aggravated murder, she allowed that he had been “dealt a lousy hand in life.” Rafferty’s mother, Yvette, was a crack addict. His father, Michael, worked the early shift as a machinist. Rafferty was basically left to raise himself, one school counselor said. Along the way, he got mixed up with Richard Beasley, a family friend–and, it was later revealed, a ruthless murderer who convinced the teenager to help him kill three men.

Under the 2021 law, Rafferty will be eligible for parole in 25 years.

Could run for president in today’s day and age.

This might sound stupid but he looks like a modern kid.

Couldn’t hack it strung himself up like a pruppet