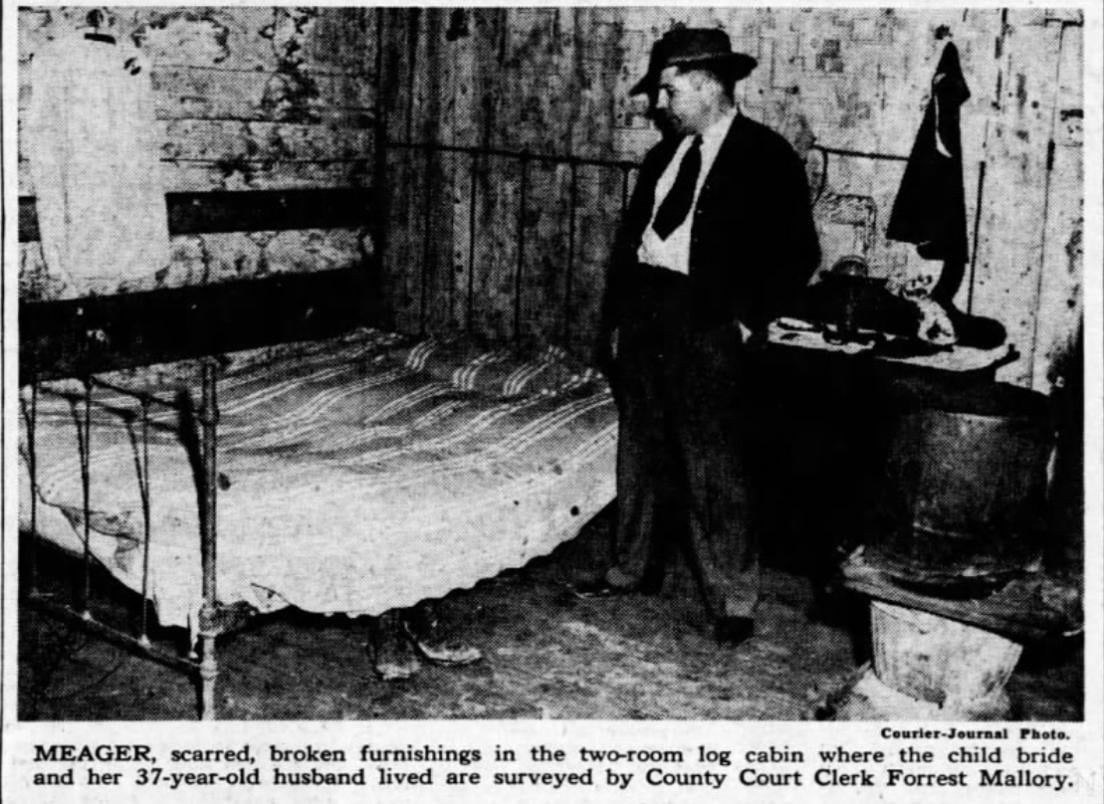

A court clerk examines the cabin where Raymond Ellison, 37, and his 12-year-old wife, Imogene Sims, lived. Ellison, who married the girl to avoid statutory rape charges, had just been arrested for murdering her. The photo was publicized by the Louisville Courier Journal, Kentucky, 1948 [1104 x 804].

by lightiggy

4 Comments

[Photos of Raymond Ellison and Imogene Ellison Sims](https://imgur.com/a/5A5MSCs)

>The child bride, a 90-pound, 4- foot-5 brunette, and her husband lived in a dilapidated two-room log house located near Ennis. The house was located in a clearing in a large tract of hills and woods. It is inaccessible by automobile. The home was furnished meagerly. In the combination living and bedroom, there was one bed, two old cane-bottomed chairs, a rickety rocking chair piled high with dirty clothes, a broken stove, a dresser, and a small table. The kitchen contained a table, two more chairs, an iron stove, a cabinet, and a homemade washstand. All the furniture was scarred. There were huge cracks in the rough plank floor and gaping holes in the shingle roof. The floors were strewn with match sticks, bits of straw, and dirt. A New Testament, bearing the name Ellison, Fort McClellan, Ala., was near the bed.

Raymond Ellison, a 37-year-old illiterate farmer and sawmill worker, lived in Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. In the fall of 1947, he was charged with the statutory rape of 11-year-old Imogene Sims. To avoid prosecution, he married the girl a few days before her 12th birthday that December. Imogene was not happy with her life. She told several neighbors that Ellison “talked to me like I was a dog” and she wanted to return home to her parents. Imogene was last seen alive on March 26, 1948. That evening, Ellison reported to a neighbor, Percy Beliles, that she was missing. The girl was not at her father’s home, either. Beliles suggested that they get bloodhounds and form a search party.

Ellison said he had no money. When Beliles offered to raise the money, Ellison said he did not want to do it and used these words, “I done looked at the electric chair once. The least I can have said about it, the better I can be.” When Beliles suggested organizing a searching party, Ellison said, “I don’t want to do that. Me and you can go over there and look around.” Nonetheless, a search party was formed. During the search, Ellison told his niece that the girl would never be found. When she said he was wrong, he replied, “Yes, I guess that is so, but if they find her in the river, how are they going to prove I was the one that done it. It is hard to prove anyone done it when nobody seen them do it.”

When it was announced that the search party would be scouring Mud River, Ellison turned himself into the county jail. He told another man, “I may be alive, and she may be dead, but when she was (is) found I guarantee she will have nothing in her mouth — no rags in her mouth.” He maintained his innocence, but feared mob violence if the girl’s body was found in the river. On April 5, Imogene’s body was found in the river. She had been strangled to death with a rag around her throat after being hit in the head with a blunt instrument.

Ellison was charged with murder. He went on trial in September 1948.

Several witnesses testified against Ellison, disclosing the numerous incriminating statements that he’d made. Percy Beliles testified that Ellison had previously told that he “going to get rid of her some way or another, very soon.” Ellison had said this only a few days before the murder. While the search was in progress, Thomas Givens testified that he saw a fire in Ellison’s garden. A cloth was found in the ashes. A merchant recognized it, saying it belonged to a coat that he’d sold to Imogene. Several days after Imogene’s disappearance, a pair of wet trousers had been found in Ellison’s home. Sheriff Otis Robinson testified that Ellison said his house had been leaking. Ellison had then made a contradicting statement to the county attorney, saying that he’d washed the trousers the previous midnight.

Robinson also testified that he’d found the tracks of a man and a child, following from Ellison’s home to the river. Ellison’s shoe size matched the man’s tracks and Imogene’s shoe size matched the child’s tracks. Two other men testified that Ellison had told them he was going to get rid of the girl “when the nine months were up.” Charles Taylor, an ex-convict, testified that Ellison had said to him, “They can make me marry her, but they can’t make me keep her.” Ellison did not take the stand and offered nothing in his defense, but objected to the prosecution twice. He objected when the prosecution informed the jury that he had married the girl to avoid statutory rape charges. He also objected to the introduction of a photo of Imogene Sims in her coffin, taken just 15 minutes before she was buried.

On September 21, 1948, after deliberating for 20 minutes, the jury found Ellison guilty of murder and fixed his sentence at death. In his appeal, Ellison raised two objections: The verdict was not supported by evidence and was the result of passion and prejudice, and certain evidence was wrongfully admitted against him.

On October 11, 1949, the Kentucky Court of Appeals (which functioned as the state’s supreme court prior to 1975), upheld his conviction and sentence in a 4-2 vote, with one justice absent. In summary, Chief Justice Porter Sims (unrelated to the victim) stated that the “evidence is wholly circumstantial,” but substantial. Objections to certain pieces of evidence were dismissed. In regard to the introduction of the statutory rape charges, Justice Sims stated that it was allowed since it was relevant to the case. In regard to the photo of the victim in her coffin, Justice Sims stated, “There is nothing sensational or shocking about the picture although it shows several wounds and abrasions about the head and face.” He conceded that the photo shouldn’t have been introduced, as he found “no reason for it being introduced except to arouse passion against the perpetrator of the crime.” However, Justice Sims stated that this error was not sufficient to reverse the judgement.

To put it bluntly, there were only two ways that Ellison’s trial could’ve ended:

>Under the record before us we do not see how the jury could have returned any verdict except-of acquittal or one inflicting the death penalty, as there were no mitigating circumstances. Therefore, we do-not think the introduction of this photograph prejudiced the substantial rights of accused.

Lastly, Ellison insisted that he couldn’t have received a fair trial in Muhlenberg County due to the public anger against him in the area. Justice Sims dismissed the concern, stating that neither Ellison nor his attorneys ever once requested, let alone applied for a change in venue. With that, the appeal was concluded. After petition for a rehearing was denied on January 24, 1950, Justice Sims fixed his execution to take place in 30 days, in lieu of any further appeals. Ellison still had the options of appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court or asking Governor Earle Clements to examine his case, but did neither. As such, the date stood.

[Ellison at the Kentucky State Penitentiary](https://imgur.com/a/6cwmxd5)

On February 21, Warden Jess Buchanan reported to the state welfare department Raymond Ellison was set to become the first person ever sent to the electric chair by Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. Nobody had been executed for a crime committed in that county in over 40 years. Attorney General A.E. Funk said no other legal efforts were being made by Ellison. Governor Clements had not intervened. Ellison had spent much of his final days with Reverend H.R. Early, the prison chaplain, and was baptized about a week before his scheduled execution.

On February 24, 1950, Raymond Ellison, 39, was executed by electrocution at the Kentucky State Penitentiary in Eddyville. His last meal consisted of fried ham, soft biscuits, soft scrambled eggs, and coffee. The warden described Ellison as mostly resigned to his fate, but still defiant. To the end, he was still hopeful that someone would intervene, and every conversation that the two had ended with the same result. A reporter said that in her view, Ellison genuinely believed in his own proclaimed innocence. She reached that conclusion after the warden asked Ellison whether he wanted to make a final statement.

>”Yes, I do. I want to thank the Lord for saving my soul. I am an innocent man. I hope the Lord will forgive the guilty one. And I want to tell another thing. I hope that the one who did this will realize what they have done and that they have killed an innocent man. I don’t blame you for this. I know you have to do this. May God have mercy on all of you. I never thought I would sit in this chair, but I know that I will go from here to Heaven.”

Poor kid never had a chance. Betting her family was no better if they allowed her to go with him.

Raymond Ellison was executed on 24th February 1950 at the Kentucky State Penitentiary. [Death Certificate ](https://images.findagrave.com/photos/2022/244/142732756_212e060a-e7a9-4bb1-8a83-7a1fdf0cc25c.jpeg)

yes honey, you need to marry your rapist so he doesn’t get in trouble …