Southern Pacific Railroad’s Train Number 13 grinded to an unusual halt slightly before 1:00 PM on October 11, 1923. Situated in Tunnel 13 on the Siskiyou Pass apex in southern Oregon, the train’s eighty-plus passengers found themselves in an unsettling darkness. This brief stop must have puzzled its eighty-plus passengers, but their confusion turned to shock when an explosion soon after shattered the train’s windows and filled the tunnel with smoke.

In the midst of this pandemonium, conductor J. O. Marrett, mistakenly attributing the explosion to a boiler malfunction, did his best to pacify the panicked passengers. He ventured into the pitch-black, smoke-filled tunnel towards the front of the train. It would take him several minutes to comprehend the brutal reality that a violent robbery was unfolding. Originating from Portland, Oregon, Train Number 13 was bound for San Francisco, California, carrying paying passengers, twenty off-duty railroad employees, and pulling four baggage cars.

Tunnel 13 lies just south of Ashland in the Siskiyou Mountains, a locale known for its wild remoteness during that era. The steep, twisting incline towards the tunnel necessitated additional “helper” engines to pull trains to the summit. Before the trains would approach the tunnel, they would stop at Siskiyou Station to unhook these extra engines. Following this, a compulsory brake test was conducted due to the steep descent on the other side of the Siskiyou Pass, ensuring the train would reduce its speed before reaching the east end of Tunnel 13. This routine procedure was followed without fail, except for that fateful day.

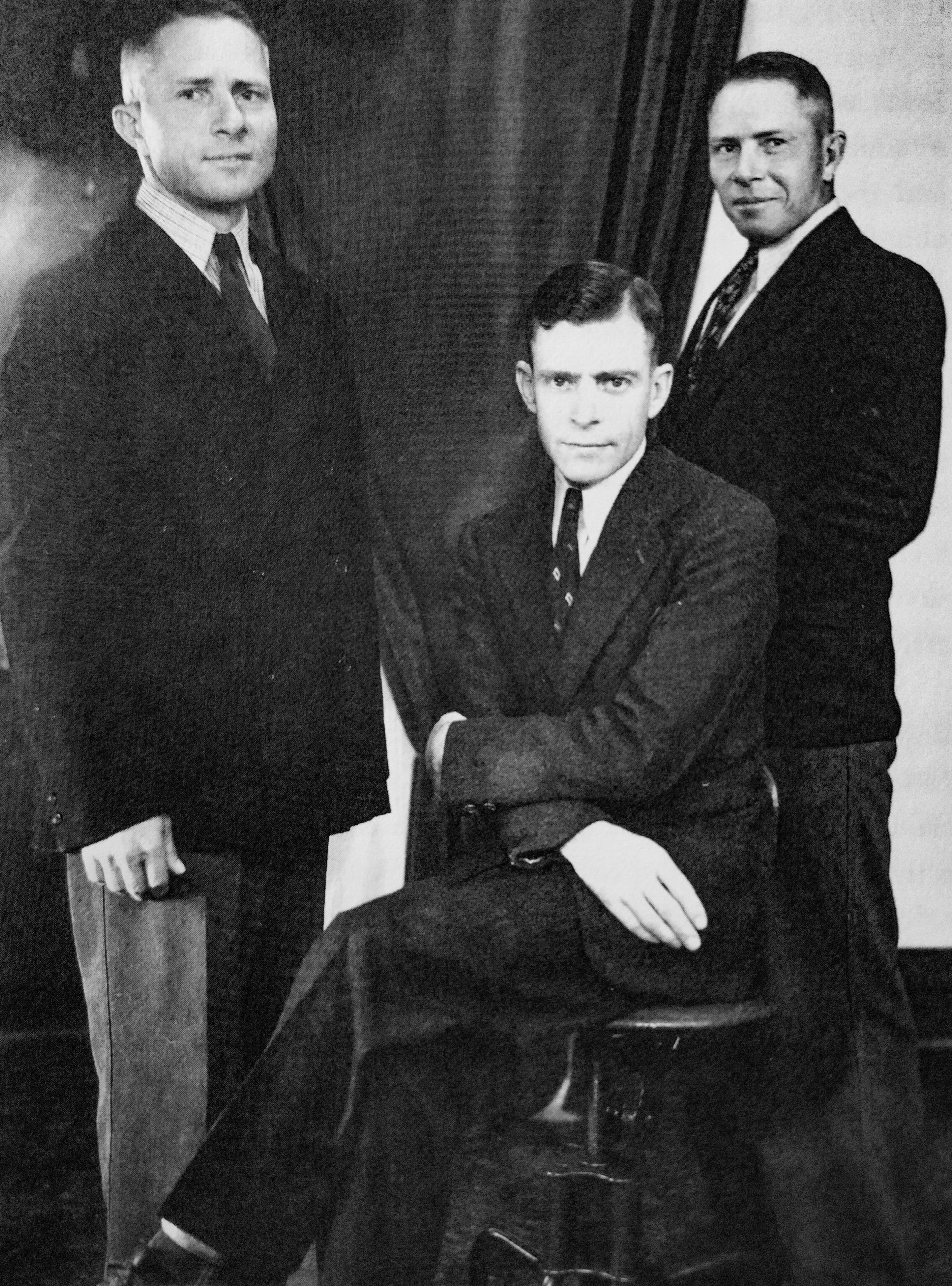

Lying in wait for the train were the DeAutremont brothers – nineteen-year-old Hugh and twenty-three-year-old twins Roy and Ray. Aiming for a monumental, one-time theft that would free them from financial worries, the brothers were staking their future on a rumor. The story went that Train Number 13, also known as the Gold Special, was carrying $40,000 in cash on this particular journey.

Their plan was straightforward. After the brake test, the train would move slowly enough for Hugh and Roy, armed with Colt .45 automatic pistols, to climb aboard. Once in the engine car, they would command the engineer to stop the train with the engine outside and the rest inside the tunnel. Ray, armed with a 12-gauge automatic shotgun, would be stationed at the tunnel’s exit to provide additional firepower if necessary. They would then blast the mail car door open with dynamite, detach the remaining train, and instruct the engineer to pull the mail car out of the tunnel. The brothers would then abscond with the cash and disappear into the mountain wilderness.

Just as planned, Hugh and Roy hopped aboard the engine car as the train approached the tunnel. They managed to take control of the engine, with engineer Sidney L. Bates and fireman Marvin L. Seng held at gunpoint, and commanded the train to halt with the engine outside and the remaining cars inside the tunnel. As the engine emerged from the tunnel and the train stopped, Ray appeared with his shotgun. When mail clerk Elyn E. Dougherty attempted to see what was happening, Ray fired at him but missed, causing Dougherty to quickly close and lock the car door. Hugh Haftney in the baggage car, who had also witnessed the scene, followed suit.

Now all the DeAutremont brothers had to do was blow open the mail car door, seize the $40,000, and make a clean escape. However, their lack of expertise with explosives led to an excessive amount of dynamite being used. The massive explosion not only blew off the mail car door, but it also killed U.S. Postal Service mail clerk Elvyn E. Dougherty and largely destroyed the mail car. The adjacent car’s baggage man, Hafney, was knocked unconscious by the force of the blast.

In the ensuing chaos, brakeman Coyle Johnson emerged from the smoking tunnel, Ray and Hugh immediately fired their guns and he dropped to the ground, wounded. Hugh walked over and shot him once more to ensure he was dead.

Assessing their situation, they realized that their loot was in flames and their escape window was shrinking. The brothers decided to kill the engineer and fireman and flee the scene. Roy shot the fireman twice in the face with his Colt .45, while Hugh executed the engineer with a shotgun blast to Bates’s head. Leaving behind four dead men, a dropped pistol, a pair of overalls, and empty backpacks, the brothers disappeared into the surrounding forest, leaving behind not only the chaos of their failed heist but also personal items that hinted at their identities.

by Defiant-Skeptic

2 Comments

The immediate aftermath of the ill-fated robbery saw relentless search parties scouring the region, with the robbers leaving no trace behind. Southern Pacific Railroad swiftly proposed a bounty of $2,500 for their capture. Fleeing from the failed heist, the DeAutremont brothers reached a pre-established hideout stocked with supplies, remaining there for approximately two weeks. Ray made an attempt to reach Eugene via Medford to secure a car, but was forced to abandon his plan upon noticing a newspaper headline – “Have you seen the DeAutremont brothers?” – accompanied by their photos. The reward for their capture, dead or alive, stood at a staggering $14,400. Returning to their hideout, Ray informed Roy and Hugh of their wanted status.

The crime scene was an investigator’s treasure trove, filled with vital evidence. Of particular importance was a handgun with a traceable serial number linking it to Ray DeAutremont and a pair of coveralls encasing the detonator. These coveralls were sent to Professor Edward Heinrich at the University of California at Berkeley for forensic analysis. Within a pocket of the garment, he found a crumpled U.S. Postal Service receipt for a letter sent by Roy DeAutremont to his brother Hugh in New Mexico. These two pieces of evidence, coupled with handwriting analysis that linked Hugh to various aliases and equipment purchases, swiftly led investigators to understand the plot. By November 23, 1923, the brothers were facing six indictments, and over two million wanted posters were distributed globally. The manhunt spanned three years and cost half a million dollars.

With leads drying up and the trail going cold, investigators were contemplating abandoning their search when a breakthrough arrived in the form of a U.S. Army corporal, Thomas Reynolds. He recognized Hugh DeAutremont, alias James Price, from a wanted poster and promptly reported it. He was found by agents of the law in the Philippines. After his arrest and a stalled extradition, Hugh was brought back to the U.S. in March 1927 and subsequently convicted of first-degree murder. Despite Hugh denying any knowledge of his brothers’ whereabouts, the renewed effort with updated wanted posters soon yielded results. Reports emerged that Ray and Roy were in Portsmouth, Ohio, living under assumed names in Steubenville. Arrested by FBI agents on June 8, 1927, they were promptly extradited to Jackson County, Oregon, to stand trial for the Siskiyou massacre. Despite the jurors’ pleas for leniency, all three brothers were sentenced to life imprisonment in Oregon State Prison, Salem.

In early 1958, Hugh was paroled, moving to San Francisco to work as a printer. He was diagnosed with stomach cancer shortly after, passing away in March 1959. Roy, diagnosed with schizophrenia and then lobotomized, was paroled and lived out his days in a Salem nursing home until his death in 1983. Ray, paroled in 1961, found employment as a janitor at the University of Oregon, passing away in 1984.

Long after the fateful day of the attempted robbery, the DeAutremont brothers discovered the grim irony that Train No. 13 had not been carrying the supposed $40,000, but only the usual mail cargo. Their botched attempt marked Oregon’s last train robbery, and today, all three brothers rest beside their mother in Salem’s Belcrest Memorial Cemetery.

They look like gospel singers!